The Bristol Parish Birth Register

Established in 1643, Bristol Parish served residents of Henrico, and later, Chesterfield County. The main church was located at Bermuda Hundred. This parish was where the Kennons of Conjurer’s Neck attended church services. Elizabeth Worsham Kennon, wife of Richard Kennon—the first Kennon to settle at Conjurer’s Neck—operated a ferry that took parishioners to and from services and she was paid by the parish, in tobacco, for the operation of that ferry. Both of her sons, William and Richard were members of the parish vestry.

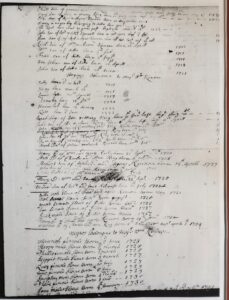

The parish vestry maintained a register of births, baptisms and death. This register was believed to have been lost to history but was found in 1894 in the library of Reverend Churchill J. Gibson of Petersburg. In 1898, the register was transcribed and put into print by Churchill Gibson Chamberlayne, The Vestry and Register of Bristol Parish, Virginia, 1720-1789. On page 52 of Chamberlayne’s work is an entry that states, “Eliz: dau: of Rich & Agnis Kennon Born 12 day decem 1720. Harry a negro boy belonging to ditto born Janr 1720.” This is an amazing find. It was not common for enslaved people to be listed in parish records of the colonial era. It was even less common for them to be listed and their date of birth noted. This is not the only instance though of this in the Bristol Parish register. On page 53 and 54 can be found the following:

Negroes Belonging to Majr Wm Kennon

Nutty born 3d octobr 1711.

Pegg born March 18th 1716.

Lewis born 20th Aprill 1719.

Annake born 14th febr 1720.

Hannibal born 17th decem 1722.

Kate born 3d June 1723…

…Negroes Belongine to Majr Wm Kennon.

Hannah female Born 2d June 1723.

Harry male slave Born 1th March 1725.

Phillis female slave Born 1th March 1725.

Scippio male Slave Born 3d March 1727.

Lucy female Slave Born 10th July 1729.

Juno female Slave Born 5th July 1729.

Sampson Male Slave Born 1 decembr 1729.

Phebe female Slave Born 2d Janr 1730.

Sam Male Slave Born 4th January 1730…

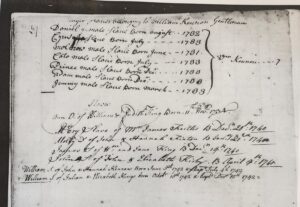

…Negro slaves belonging to William Kennon Gentleman.

Daniel male slave Born august 1732.

Cyrus male slave Born July 1733.

Molbrow male Slave Born June 1731.

Cato male Slave Born July 1733.

Prince male Slave Born Dcer 1733.

Adam male Slave Born Dcer 1733.

Jemmy male Slave Born March 1733…

William’s brother, Richard, and his wife Agnes Bolling Kennon, also had enslaved individuals whose births were recorded in the birth register.

Bille male Slave of Richd and agnis Kennon Born May 1723.

Mol female Slave Ditto Born august 1725.

Janne female slave of Ditto Born febr 1725.

Sue female slave of Ditto Born Dcemr 1727.

Dick male Slave of Ditto Born March 1727.

Something that can be gleaned from some of the names of these children (Scippio, Cato, Juno, Sampson, Prince), is a naming pattern. It is important to note that slaves, in almost all instances, did not get to pick the names they gave their children, or their own names for that matter, when they came to the colonies. Many enslavers would name their slaves after Greco-Roman characters, heroes, and authors. Susan Wegner, an Associate Professor of Art History and Chair of Department of Art at Bowdoin College, states that enslavers naming their slaves after “classical names could show off slave-holders’ learning while also mocking those humans held as property by giving them ironic names of powerful ancient rulers, gods, and heroes.” Some of the names enslavers gave to their women bondspeople, like the name Venus for example, “reflected and licensed the lasciviousness of European slaveowners toward African women, making such behaviors ‘sound agreeable,” states Sarah Abel, a cultural anthropologist.

The Bristol Parish register is truly amazing. There are twenty-three enslaved people listed in the register belonging to the Kennon family and their birth dates listed. This is a wealth of information considering how uncommon this is. There are other enslaved people listed in the register that belonged to other families as well. This begs the question, why is it that so many enslaved people, especially those of the Kennon family, turn up in this register? One answer could be that these enslaved children could be the children of household slaves, those who were closest to the family and spent the most time with the Kennons. Perhaps the Kennons felt some sort of affection or fondness for the parents of these enslaved children. Hopefully, future research may turn up more answers.

Update:

On April 16, 2025, on a visit to the Library of Virginia, the microfilmed original documents from the Bristol Parish Vestry Register were located. In discussions with a staff member of the Library of Virginia and through research, a number of reasons can be speculated as to why enslaved children’s births were included in the vestry register. It is indeed fairly rare to find this many enslaved individuals listed with dates of birth in parish vestry records. The Anglican Church of England in Colonial Virginia was the primary denomination of the colony and the most influential. Despite this though, there was no set standard for how individual parishes maintained records or what information to record. It could be that the Bristol Parish Vestry determined to record all births that occurred within the bounds of the parish, whether those births were white people, free Black people, or enslaved individuals. In some instances, parishes as a whole would sometimes purchase enslaved people as an investment. This is not the case though with William Kennon as he owned these enslaved individuals outright. Below are the pages for the birth register from the Bristol Parish Vestry Register for families whose names began with a K, listing all of the enslaved individuals of William Kennon of Old Brick House.

References

Bristol Parish Vestry. “Bristol Parish Vestry Book and register, 1720-1789”, accession 35927, Misc. Reel 1843, no date.

Chamberlayne, Churchill Gibson. Births from the Bristol Parish Register of Henrico, Prince George, and Dinwiddie Counties, Virginia, 1720-1798. Richmond: Churchill Gibson Chamberlayne, 1898.

Wegner, Susan. “Classical Names and Concepts Used in the Service of Slavery.” Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Accessed 24 July 2024. https://bcma.bowdoin.edu/antiquity/classical-names-and-concepts-used-in-the-service-of-slavery/.